President Donald Trump, flanked by members of Congress(Picture), and officials from the aluminum industry, signs a memorandum on aluminum imports and threats to national security, in Washington, April 27, 2017. The Trump administration blames China for the decline of aluminum production in the U.S., but some of America’s largest aluminum companies, including Alcoa, operate in Iceland. At the right is Roy Harvey, chief executive officer of Alcoa Corporation. Where did the United States’ aluminum smelters go

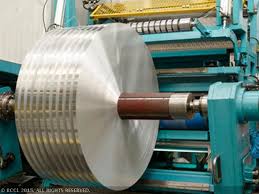

More than 30 of the giant factories once dotted the U.S. landscape, sucking down huge amounts of electricity to produce the metal for car parts, beer cans and aluminum foil. Now there are just five smelters — all facing an uncertain future. Arctic News hs made this article from Reydarfjordur on , Iceland.Cheap electricity has made Iceland a leading aluminum producer

President Donald Trump blames China for flooding global markets with subsidized aluminum. In April, he ordered the Commerce Department to consider quotas or tariffs to shelter U.S. producers from foreign competition. He promised a revival that would create jobs for «lots of wonderful American workers.» But the jobs, for the most part, didn’t go to China. U.S. aluminum was in decline long before Chinese production began to grow. The more complicated truth is on display here, on Iceland’s remote eastern shore.A generation ago, this hamlet was a herring town, a place where almost everyone made a living from the sea. Today, people work on the flats of the spectacular fjord, where America’s largest aluminum company operates its newest smelter.

Production om Iceland

Alcoa, formerly the Aluminum Company of America, and another U.S. company, Century Aluminum, have opened factories like this in Iceland, and closed factories in the United States, for a simple reason: Electricity is much cheaper here. This year, tiny Iceland is on pace to make more aluminum than the United States. So are its fellow hydropower superpowers, Canada and Norway. This is precisely the kind of globalization that economists have long told us is beneficial. Iceland gets jobs. Alcoa shareholders get higher profits. Shoppers in the United States get lower prices. Of course, there is also a hefty cost: factories closed, jobs gone, communities torn apart. Voters infuriated by the loss of manufacturing jobs helped put Trump in the White House. But in a curious twist, the U.S. aluminum industry and its workers are now hoping the last round of globalization will help the surviving companies compete against a new rival: China.

Return to Reydarfjordur

Iceland rose to prosperity by exporting codfish, but beginning in the late 1960s, officials landed on a clever way to export another natural resource: electricity. They persuaded a Canadian company to open the island’s first smelter, where aluminum is produced by electrifying molten pots of alumina, a material refined from bauxite.

The dull gray ingots are sometimes described as «packaged electricity.»

Iceland’s first smelter sits just south of Reykjavik, the capital city and dominant population center. The second, opened by Century in 1998, sits just to the north.

Alcoa arrived in 2007 after Iceland built a giant power plant on the other side of the island, near a sparsely populated region where the fishing industry was in decline.

Iceland’s electric utility built five highland dams that capture glacial meltwater. The largest of the resulting reservoirs is roughly the size of Manhattan. The water is piped 25 miles to an underground power plant, then dropped a quarter-mile down another pipe to make the turbines spin. Finally, the resulting electricity is transmitted 47 miles on high-voltage lines to the ocean’s edge.

Cost only one third

Electricity in Iceland costs about 30 percent less than what Alcoa might pay in the United States. That’s a crucial consideration, because the Alcoa smelter alone uses more than 5 million megawatt-hours of electricity each year — about the same as the half-million people and all the businesses in the city of Colorado Springs. Alcoa chose Reydarfjordur also because of its deepwater port, which the United States used as a military base during World War II. Lower shipping costs have played a key role in allowing smelters to be built in the far corners of the earth. It is more difficult to get here by land. The road from the nearest airport is sometimes closed in winter. The long smelting sheds are bound together by large, colorful pipes, and, because this is Scandinavia, the company held an architectural competition for the design of the administrative wing. The complex, where 450 people work in two shifts, is probably the largest in Iceland.

Was a Ghost Town

Olafur Gunnarsson, 33, an Alcoa employee, was raised here. When he was a toddler, herring was king. But then he grew up, the fishing companies left, and nothing else came. He drove a truck, worked briefly at the post office, got a job at the grocery store — and quickly lost it because there weren’t enough customers.

«This place was going to be a ghost town,» he said to Arctic News.

Then Alcoa arrived, and with it, his first steady job. He has worked at the smelter for 10 years and has a 7-year-old daughter. «That was the best thing that happened to this town,» he said. «New life and new people.»

Sandra Thorbjornsdottir, originally from Reykjavik, moved here in 2010 to reopen an old inn, Taergesen, that had closed the previous year. She has prospered as the town has revived. In 2013, she added a second building of guest rooms. Last year, she bought another nearby hotel.

And while Iceland is exporting aluminum to the world, she is importing all of her workers. At the moment, her three guesthouse waitresses are Polish, French and Spanish.

The population, which had fallen to about 600 from 1,100 by the early 2000s, has rebounded completely.

Thoney Kristin Sveinsdottir arrived in Reydarfjordur at 17, when her father took a job at the fish processing plant. She and her sister both left town as quickly as they could, but now they have both returned. She married a man who works at the factory, and her sister works in Alcoa’s local office.

«If the factory wasn’t here, I wouldn’t have come,» she said. «I think Alcoa saved this town.»

Photo:(Stephen Crowley/The New York Times. )Author: Binyamin Appelbaum, The New York Times Updated: July 3 at 8:51 AM Published July 3 at 7:53 AM. Arctic News.